Since the annual San Donnino festa is likely to be part of our life, and therefore of this blog, for some time to come, it seems like a good idea to present the details of his story all in one place, instead of continuing to dribble them out a bit at a time, as I've been doing. Here, then, is the man behind the holiday.

San Donnino, a.k.a. St. Domninus, is a distinctly minor figure in Catholic hagiography, pretty much unknown anywhere but Northern Italy. Therefore there's very little solid information about him; this is more legend than history. Domninus was born in Parma sometime in the second half of the third century CE and became a high official in the Roman hierarchy, serving as chamberlain and keeper of the royal crown to Emperor Maximian.

A bas relief on the front of the Fidenza Duomo, below the figure of St. Simon Peter pointing the way to room, shows Domninus placing the crown on Maximian's head, apparently one of his daily duties.

|

| You can see Domninus crowning Maximian in the lower right. |

Maximian and his co-emperor, Diocletian, were pagan conservatives and in 303 CE they launched a vigorous campaign of persecution against Christians and other religious minorities. Christians were purged from the military, their churches were destroyed, their property was seized, and those who refused to make sacrifice to the Roman gods were sometimes put to death.

This didn't stop Domninus from secretly converting to the Christian faith. But in the year 304 Maximian discovered his chamberlain's heresy and ordered his execution. Domninus fled but Maximian's troops caught up with him just outside of what was then the Roman town of Fidentia as he was about to cross the river Stirone. They seized him and cut off his head.

But empowered by his Christian faith or some autonomic nervous response, Domninus rose up, picked up his severed head, walked across the Stirone. and lay down on the ground on the other side, cradling his head in his arms--a rather pointless gesture, but clearly miraculous.

Another bas relief on the front of the cathedral shows Maximian wielding a sword on the left, on the right Domninus crossing the river with his head in his arms, and, in the center, the headless martyr being elevated to sainthood by two angels.

|

| Interesting use of non-chronological storytelling. |

A few decades later the bishop of Parma dreamt that a saint was buried in a spot by the Stirone, next to a brick inscribed, "Here is hidden the body of St. Domninus, martyr for Christ." With the assistance of this rather obvious clue, San Donnino's relics were found. The persecution of Christians having eased under the new emperor, Constantine, a small church was erected in that place to house what was left of the saint, whose name by now had been Italianized to San Donnino.

One day a man came to where San Donnino was buried to pray for help. His horse had been stolen and he wanted it back. Lo, the horse was returned.

Walking while decapitated is certainly impressive, but not particularly endearing, and the miracle of the stolen horse seems to be neither. Nevertheless, San Donnino attracted enough devotees that the church had to be enlarged. over the next century or so. In the process it was noticed that, although the church had been built over the saint's remains, no one had kept track of exactly where they were. But a priest, inspired by divine intuition, discovered the saint's relics underneath the church in a sarcophagus labeled, "Here lies the body of the most blessed martyr Donnino." Again, this seems more obvious than miraculous, but perhaps you had to be there.

|

| A more recent portrait of San Donnino inside the cathedral. |

Donnino's posthumous popularity grew and more and more pilgrims began coming to pray in his church. So large were the crowds that one day as a group of pilgrims crossed over the Stirone the wooden bridge collapsed beneath them. "But--a miracle!--thanks to the intercession of San Donnino no one was hurt, including a pregnant woman on whom numerous other people had fallen," reports the Fidenza cathedral's website.

|

| The pregnant woman and the collapsing bridge, also on the cathedral facade. |

This painting, by Cristoforo Savolini, shows Saints Borromeo and Appolonis (two other C-list saints) flanking Saint Domninus, who wears the outfit of a Roman centurion. I assume the dog is there because of the Fidenza saint's anti-rabies powers, although to me he looks not only non-rabid but like a very good boy.

Poor San Donnino's remains were once again mislaid when some unspecified enemies of Catholicism razed the church in the 600s or so. But in the eighth century Charlemagne was en route to Rome to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor when (the story goes) his horse abruptly stopped at a spot by the Stirone and refused to go any farther. An angel appeared and told the soon-to-be emperor to dig for treasure in this spot. The treasure turned out to be San Donnino's relics.

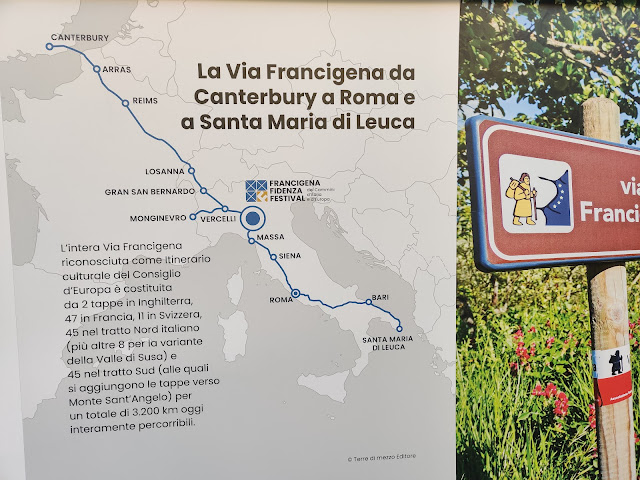

In a smart piece of medieval marketing, the village (borgo) where all these things occurred renamed itself Borgo San Donnino, and the structure housing the saint's remains became ever grander. In the 1100s construction of the present Duomo began and continued for a century and more. The cathedral became an important stop on the Via Francigena pilgrimage route, and the sculptures decorating the facade include not only images of the saint and his martyrdom but also numerous depictions of pilgrims making their way to Rome and the Holy Land.

Inside the cathedral is San Donnino's sarcophagus, which also features bas reliefs of his martyrdom and his miracles. Below the statue of the headless saint, the panel on the right shows, again, San Donnino crowning the Roman emperor. I'm pretty sure the panel on the left depicts the man praying for the return of his horse.

|

| You know it's him because his head is on his chest. |

In the 1920s, when Mussolini's regime was seeking to rebrand Italy as Imperial Rome 2.0, the town fathers decided to change its name from Borgo San Donnino to Fidenza, a phonically updated version of the old Roman name.

The saint and his cathedral nevertheless continue to loom large in the city. The Duomo is the city's most distinguished architectural feature, and although it's quite ascetic compared to the gaudy cathedral extravaganzas in many other Italian towns, here in Fidenza it's one of the few things of any interest to tourists. San Donnino's legend is part of the cathedral's appeal, and the town's, if only because it's so old and so odd. And the annual festa in the saint's honor is Fidenza's biggest event of the year and a source of community pride and pleasure.

Whether or not San Donnino really carried his head across the river, whether or not he cured rabies or restored stolen horses to their owners, nowadays he is certainly doing a lot for Fidenza. It's no wonder they love him for it.